I have a long history of loving trading card games.

From slamming Duel Masters cards on concrete when I was younger, to levelling up into playing Magic: the Gathering’s Legacy format, to hosting podcasts, to writing weekly articles and more recently being a Human of Magic (thanks James!), trading card games have always had a special place in my life. A constancy I can always return to when I am looking for a particular feeling and expression of who I am.

Like many other Magic-obsessed university students, I spent countless distracted lectures crafting new deck lists, sending them to my friends to responses of “that’s a terrible idea” and then testing via jamming lots of games. And then honing, refining and coming to a conclusion. Sometimes “damn, that was a terrible idea” or other times “hm, I’m on to something!”

Only recently I’ve realised this approach to building decks has shaped how I approach life and solve problems. It’s carried on into how I think as a designer.

All deck building can be founded on:

Problem-solving how to execute a particular strategy to win the game

Creatively bringing together ideas to solve the problem

Testing and experimenting

Collaborating and discussing to get feedback

And… Eventually shilling out a bunch of money to buy cardboard.

For this article, I’ll be going through the good ol’ Double Diamond process, but look into how I ended up practising this via building and testing Magic: the Gathering decks.

I hope this article makes many Magic players, or any other trading card game players, realise: you’re a designer, you’re a creator, you’re a problem solver.

And those countless notepads scribbles with deck lists aren’t a waste of time. They’re practising how to think critically, how to go deep on research, how to hone options and experiment to solve one of life’s greatest challenges. Winning a game of Magic and having fun while doing so.

Remembering the Double, or Triple, Diamond

Some of you may already be aware of the Double Diamond, but I think it’s worth reiterating. If you’ve already heard of this before, feel free to skip to the next section.

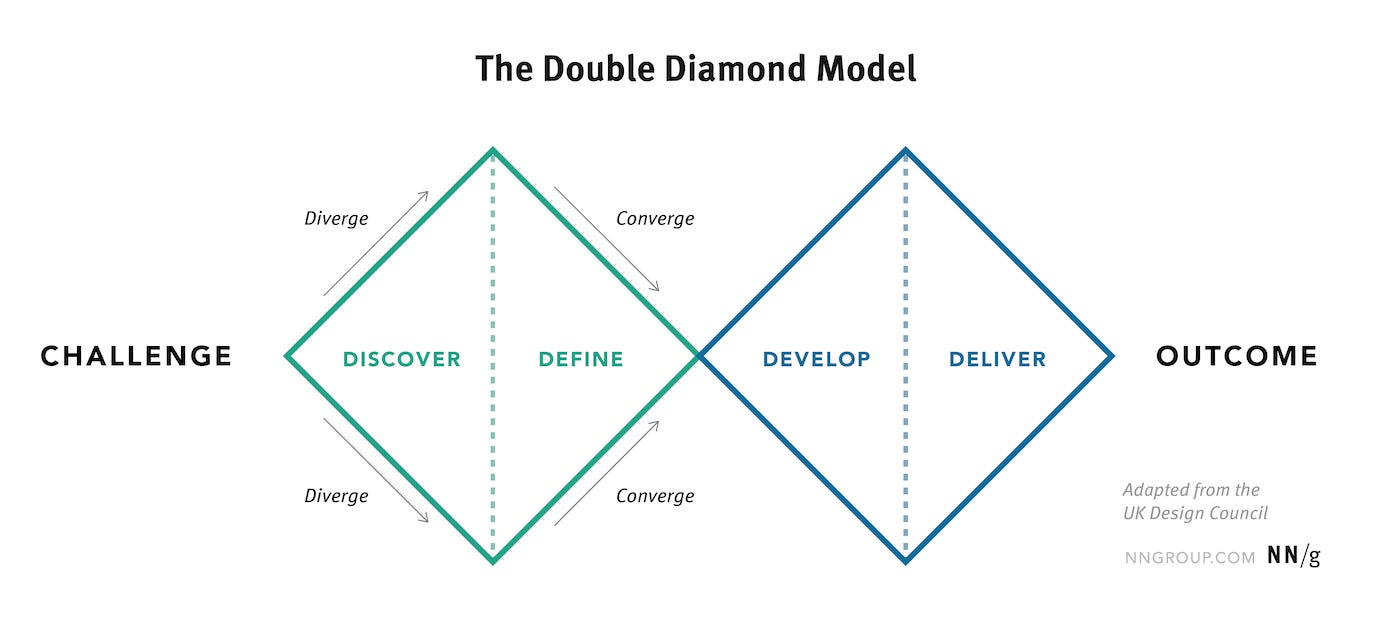

The Double Diamond is a framework developed by Design Council UK for solving problems, particularly applicable to product design, but broad enough to encompass almost any problem, including our topic today of MtG.

There are four key phases of the model, each focussing either on divergent or convergent thinking. It’s also expected that you will ‘loop’ inside each of the diamonds before you move forward.

Discover: Open up the problem space and question everything. The key here is to go wide and challenge every assumption. This step is plenty of research, plenty of interviewing and plenty of throwing ideas on to the wall.

Define: Start to boil down everything you’ve found in the discover phase into something with more clarity (eg. a problem statement). It can still be a little fuzzy — that’s okay. We can loop back into discovering further if we’re still not quite there.

Develop: Start to build different solutions to the problem. The more you build, the better.

Deliver: Test your various solutions at various scales. Be ready to go back to the Develop phase, or even the Discover phase, and iterate, iterate, iterate.

Now, don’t get me wrong, this model has been around since the dawn of the ‘Design Thinking’ revolution and it’s come under some heavy scrutiny in recent years (see, for example, here and here). There’s a bunch of alternative, more nuanced models out there you can look into which avoid what some perceive as the Double Diamond’s oversimplification of the design process; I’m particularly fond of this ‘Triple Diamond’ by Thomas Wilson.

Anyhow, we’re going to be paralleling the Double Diamond with how I’ve been building Magic: the Gathering decks. Strap yourself in.

1. Discover

I find the Discover phase one of the most enjoyable, but stressful parts, of building a Magic deck, as you’re in the wild west of working out even where to start. Let's have a look at this in context, using an Australian Highlander deck of mine as an example.

Australian Highlander is a singleton sixty-card format with a points list that defines how many powerful cards you can play. This makes it a brewer’s paradise (similar to other singleton formats like Commander and cEDH).

The deck we’ll be looking at is Strawberry Shortcake, whose primary goal we will be shaping our Discovery phase around:

To win the game via the Painter’s Servant / Grindstone or Auriok Salvagers / Lion’s Eye Diamond combo.

I’ve quickly given us a relatively defined goal, unlike the Discovery phase of a product, where starting with a defined goal is a big no-no. Rather, you should start with a much, much broader goal and then question and optimise from there. In the context of Magic, our broad goal might simply be “win the game”.

So why have I made this so narrow?

Magic, since it is ultimately a hobby, gives us the liberty to have self-expression and fun be part of our end goal. These two combos are some of my favourites in the history of the game, and finding a way to have these two work synergistically sounds like a delightful problem to solve. Running this through the Double Diamond and exploring this interaction is a joy in itself — even if it might not mean winning all the time.

On to the actual how of Discovery. And it is all about research, research, research. With Magic, resources come from sites such as MTGTop8, MTGGoldfish and databases such as Moxfield. I find cards across all the various formats of Magic and pool them into a huge list of cards (I love Moxfield’s Considering section), not worrying too much about how they fit together. Rather, this is just about gathering as many ideas about how we can support our goal.

It’s also important to engage with other Magic players around these ideas. And this is one of the joys of Magic. Bouncing ideas between friends and them recommending “hey, this card would be great for your deck!” further shapes your pool of ideas.

And so we get to our big superlist of cards. Notice I’ve already started the Define stage somewhat by narrowing down to two colours. You can only have so much time! If I wanted to revisit additional colours I could look towards this in further iterations.

2. Define

Defining is all about taking this research, this big messy stew and turning these into insights. It is about turning something fuzzy, vague and expansive into something more focused and sharp. This is the moment to connect the dots, link those sticky notes together and start to see what the true challenge, and hints of the solution, actually are.

For our Magic example, we can start to link together particular interactions and synergies, cluster groups of cards together and refine our core strategy

Here’s what I found during the Define phase for our Strawberry Shortcake deck.

We’re a combo deck, so we need ways to find our combo.

Especially in a singleton format like Highlander, redundancy is incredibly important. Cards like Urza’s Saga, Imperial Recruiter and Enlightened Tutor are key additional pieces of the combo.

We need ways to recur and revive our combo creatures.

Our creatures are quite fragile, so it’s highly likely they’ll get countered or just die. Cards like Goblin Welder, Goblin Engineer (serving double duty as a tutor, too) and even unlikely heroes like Extraction Specialist all serve to remedy this and provide redundancy.

We’re heavy on artifact synergies.

With both combos being artifact-reliant, anything that has artifact in its text or generates artifacts are at a premium. We’re getting a lot of power from synergy here, rather than raw power.

We value cantrips and deck-thinning.

“Cantrips”, cards that cycle themselves, are an important piece of the puzzle, as with Auriok Salvagers they allow us to draw our whole library. They also keep our curve low and ensure we can find our combo pieces more readily, as we have essentially a reduced deck size.

Now that we’ve given our deck’s goals, and sub-goals, some more clarity, it’s time to refine our long list of cards further, judging what fits with our game plan, clustering them into various roles and then moving towards the Develop phase. I typically do this by working through my consider list and starting to move cards to the main deck.

3. Develop

Develop means finally sculpting this into a decklist. Taking those thoughts and ideas and actualising them into sixty cards.

Magic, like design, has frameworks and heuristics for what works. Just like how an 8px grid is recommended in UI design, Magic has heuristics ensuring you can cast your spells in a timely fashion and your deck operates like a well-oiled machine.

For this deck, due to the high amount of cantrips and acceleration, and a maximum mana cost of four, I’ve opted for twenty lands, a bit lower than the typical twenty-four. These are composed of traditional coloured mana sources, alongside utility lands such as Inventors’ Fair and Buried Ruin.

With that restriction in mind I’ve got forty other slots to play with. I’m trying to keep a relatively tight curve for this deck, since ultimately we are a combo deck, so I’ve prioritised low-cost artifacts and saved the four drop spots for absolute game-winners such as Salvagers and The One Ring.

And there we have it! A deck that’s built on a solid foundation of Discover and Define. Time to spend some money and buy cards.

4. Deliver

And time to Deliver! This means: no more thinking, time to start playing!

As much as I enjoy the process of thinking about Magic, there’s something special about that moment you bring a brew to an event and see it in action. It’s even more satisfying when you win, but that doesn’t always come easily. That’s where iterating, refining and continually questioning the ideas you have come into play.

For example, realising that our deck struggles with common sideboard cards like Collector Ouphe, or even main deck cards like Karn, the Great Creator, means we need to have both ways to react to these cards and secondary plans to push through them.

You might track this via a spreadsheet (like me, I’m nuts) or just take mental notes as you play through games. It’s up to you. But it’s important to be willing to slay all the assumptions you’ve built up throughout the previous stages and be ready to go back to the Discover drawing board again.

But if you’re anything like me, then that idea is fun. That continual process of testing, revising, re-researching and rebuilding is what makes Magic, and many other trading card games, so enjoyable.

And in the same way, it’s also what makes design so enjoyable to me, and why I’ve decided to make it so intertwined with both my career and who I am.

That process of creating something to solve a problem, it makes me happy.

Hopefully, you found this exploration as fun as I did and I haven’t alienated too many non-Magic players (sorry for all the jargon!).

But I’m sure everyone has their hobbies or experiences that helped them realise their path to design. Magic is mine, and I hope you enjoyed my sharing of it!

Finishing with a quote, as always.

“I’mma keep running, cause a winner don’t quit on themselves.”

— Beyonce, Freedom