Inspired by Filipino art and design

How connecting to your roots can be a wellspring of inspiration.

Inspiration can be found in the most unlikely places.

I’ve been going on a journey of reconnecting with my Filipino roots. This can mean a bunch of things, from eating tonnes of adobo, to spending time with family, to listening to Pasilyo by Sunkissed Lola on loop.

But I, unfortunately, didn’t have high expectations for visual inspiration — be it design or artistic — when it came to the Philippines.

Perhaps this is part of the continual Filipino, or even South-East Asian, inferiority complex we have when comparing ourselves to the rest of Asia. An assumption that not just aesthetically, but culturally, neighbours in East Asia, such as Japan, Korea and China, have a lot more to offer.

Earlier this year, I spent time in Japan and South Korea, engulfing every bit of inspiration I could find, from Japan’s usual retro quirkiness, to design galleries in Ginza, to Dongdaemun Design Plaza in Seoul. It was satisfying. I felt full of inspiration and design books that I couldn’t read.

After this, I spent time in the Philippines, primarily to be with family, with expectations of dusty streets, sari-sari stores and typography appropriated from American burger joints. Low expectations for visual inspiration all around.

But my eyes started to open. With my adult eyes, things I’d seen in childhood were now re-contextualised into the strange, inspiring tapestry that is the Philippines’ visual style, crafted from a culture holding on to its own identity through persistent colonisation. No longer kitsch, but a part of who I was, that I wanted to make part of my identity as a designer, and something precious that I wanted to share with the world.

And that’s why I’m writing today.

Design in the streets

Although I ended up at a bunch of beautiful museums and galleries around the Philippine, where I found the most inspiration was from the typography, buildings and signage around everyday streets.

Something as commonplace as the Filipino jeepney is a poster child for what the Philippines’ visual style is. Born from repurposed military vehicles, Filipino jeepneys are plastered with graffiti-esque vibrant colours, illustrations that are a grab-bag of influences from across the Philippines’ history — from Jesus with his bleeding heart, to Goku from Dragon Ball Z — and uniquely stencilled typography.

I’m particularly fond of the typography, especially the more functional text used to denote the destination of each jeepney (though I can still barely work out how to use the public transport system in the Philippines). When I see these typefaces, replicated beautifully by Filipino type designer John Misael Villanueva with BBT Martires, I feel hints of Spain and European illuminated manuscripts, but repurposed for the everyday Filipino’s practical use.

Beautiful type is everywhere. From transport terminals to shops, there’s a beautiful combination of bold blocky forms, to lovingly crafted scripts and serifs. I can’t imagine the time and labour that goes into not only developing these signs, but also developing the skills needed to consistently replicate these forms.

Luckily for those of us working with digital type, there are plenty of Filipino designers who have been bringing this typography to the wider world. In addition to John Misael Villanueva, Aaron Amar similarly has brought authentic Filipino sign typography to life with Quiapo, Dangwa and Kawit.

Going back in time

As a youth, I found myself disliking Catholic religious imagery. Beyond the frequent depictions of blood and suffering, there was a certain kitsch, uncanny valley quality to it that I couldn't shake off. When I looked at statues of bloodied Jesus Christ on the cross, I often felt afraid. Furthermore, Catholicism as a faith ceased to resonate with me at an early age.

But now my appreciation for Catholicism has evolved beyond religious narratives to its broader cultural context. I've grown to value how its traditions and imagery are intertwined with the very essence of Filipino identity. As I rode my bike around busy streets, I was greeted at corners by the Virgin Mary, illuminating my path. And I couldn’t help but smile.

There were plenty of churches around the Philippines I visited, with plenty of statues to go with them, but I was most impressed by the museum within the San Agustin Church, Intramuros. Displaying such a broad collection of statues, many in different stages of disrepair, highlighted the human touch behind them, crafted through the ages — some of them looking to replicate European images, others attempting to produce something distinctly Filipino.

It’s also easy to forget the early Hindu and Islamic roots of the Philippines, which are luckily preserved and explored in the Ayala Museum in Makati. The kinnari (from Hinduism) and the Buraq (from Islam, Mohammed’s steed on his night journey) tickled my usual inclination towards chimeric creatures.

Last in our little historical journey, I’d like to talk about the Boxer Codex, created around the 1590s. Likely crafted by the Spanish during their initial encounters, the Codex recorded their observations of the diverse peoples throughout the archipelago. The Codex showcases the uniqueness of each ethnic group via bold colours and dignified poses, surprisingly without little evidence of denigration. It’s a fascinating time capsule, offering insight into how these soon-to-be colonisers perceived pre-colonial Filipinos.

The influence of Japan

Japan, particularly post-war Japan, brought the Philippines all the bright characters of Japanese pop culture. Anime such as Slam Dunk, Ghost Fighter (ie. Yu Yu Hakusho) and Detective Conan were all staples of Filipino TV whenever I visited as a child, all dubbed into Tagalog. As aforementioned, these characters often ended up plastered on jeepneys and paraded around the streets, now engrained in the culture itself.

But my recent trip made me aware of Voltes V. Airing around the end of the 1970s, during the era of President Ferdinand Marcos, Voltes V is a pretty run-of-the-mill Japanese sci-fi mecha anime.

But in the Filipino consciousness, it has become a lot more.

In the Philippines, Voltes V was taken off-air by the President’s decree due to its apparently violent nature. But most agree that the dictatorial government didn’t want the show’s themes of rebellion and freedom percolating into the minds of the next generation.

And so, Voltes V is no longer just a Japanese anime. In the Philippines, this show, from another country once our oppressors, has become a symbol of resistance, freedom and anti-authoritarianism. To me, this represents the unparalleled flexibility of the Filipino culture to remix outside influences and channel them into a cause for a better future.

The Philippines’ lasting connection to Voltes V was further reemphasised by the live-action remake of the show that aired on GMA this year. I was also really inspired by the sculptural work of Toym Imao’s Super Robot — Suffer Reboot series, blending classical triptych forms, religious parallels and all of the cancelled super robot shows to make a burning commentary of the Marcos era and the lasting effects of dictatorship.

And America

It’s sometimes easy for me to think of America as just bringing along the commercialist engine of hamburgers, pizzas and soda, ruining the Filipino diet. Visual designs dominated by big, bold, chunky typefaces telling you to go eat fast food. But there’s a lot more than that.

The street culture of America, particularly African-American culture, has left a huge imprint on the Philippines, from the basketball jerseys everyone wears to a growing street art culture and love of hip-hop.

American culture also influenced Filipino aesthetics through pop culture like comic books, movies and TV, like the rest of the world. But in Australia, we definitely weren’t getting anything like these.

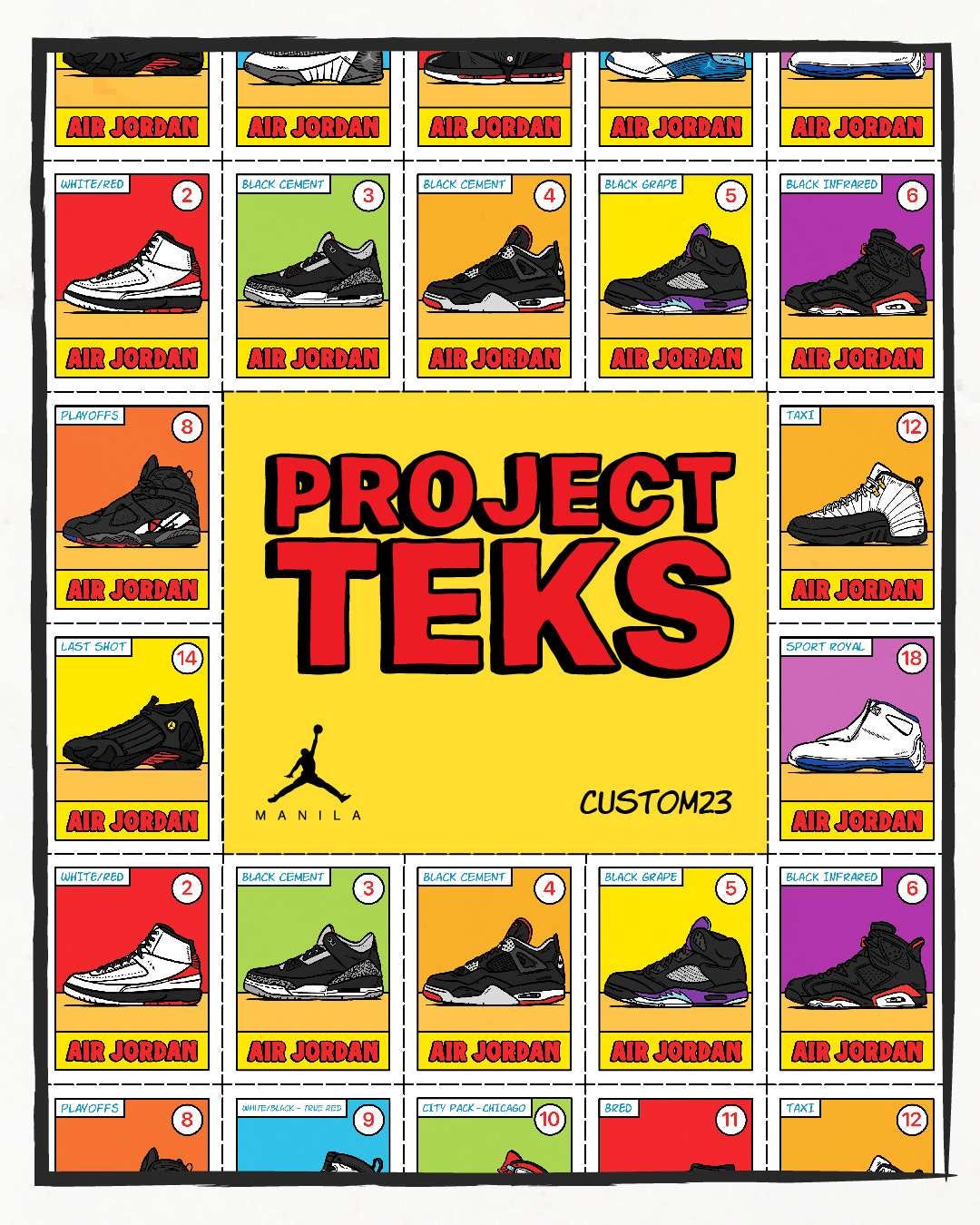

Teks were compact cards, just a quarter the size of a standard playing card, adorned with images ranging from comic book panels to movie stills to anime scenes. Incredibly cheap to produce and buy, these were often fought for by kids in streets and schoolyards by flicking, flipping or trading them.

I recently went to the Air Jordan store in Manila and got exposed to Bijan Gorospe and his work on Project Teks. I even bought a shirt. Bijan’s doing amazing work reviving the aesthetic of teks, which have been produced in the Philippines since the 50s, but are largely losing their appeal in the digital age.

But teks harken back to a more simpler, nostalgic time. In reviving the aesthetic, and showing how new trends can be appropriated into these, Bijan’s tranforming these small, yellowing pieces of cardboard into a timeless, uniquely Filipino aesthetic.

Thanks for joining me on this journey through the rich tapestry of art and design in the Philippines!

In writing this, I feel not only closer to the heart of Filipino artistic expression, but also to the socio-political challenges the country has faced and continues to face.

As a member of the diaspora, I want to channel these insights into whatever I create, reflecting the Philippines’ identity but also the country’s unique challenges.

I hope this journey inspires you to delve into the depths of the Philippines or perhaps take a closer, more personal, look at your own cultural roots.

Signing off with a quote, as always.

While a people preserves its language, it preserves the marks of its liberty.

—Joze Rizal, El filibusterismo

Great to see the visual art! And Voltes V references too. I always felt the Philippines had a great wellspring of artistic talent, from jeepneys to t-shirts celebrating Cory Acquino